Dunbar

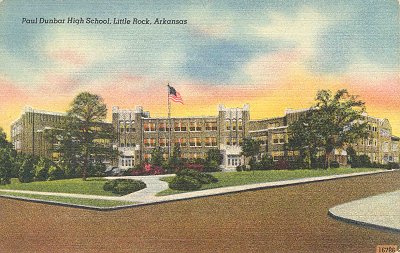

Dunbar opened in 1929 and was named for Paul Laurence Dunbar (1872-1906), the first African-American poet to gain worldwide recognition. After Little Rock [Central] High Schoolwas completed in 1927, School Board member G. DeMatt Henderson, Sr., believed that a new high school for African-American students also should be built. He went to Chicago at his own expense and secured a grant from Sears, Roebuck & Co. executive and philanthropist Julius Rosenwald to help fund the construction of this new school. The Julius Rosenwald Fund financed, among other projects, the construction of nearly 5,000 schools for African-Americans in the South. (Many of the "Rosenwald schools" have vanished, and many more either are abandoned or are functioning in other capacities. Dunbar is distinctive as a thriving, prospering educational facility that has adapted to its community [a segregated school, an integrated school and now a magnet school]).

This new school originally was named the Negro School of Industrial Arts and was a junior-senior high school that offered general education, trade classes and college preparatory courses. It opened in 1929, and its official dedication took place on April 14, 1930. It also housed Dunbar Junior College in one wing. The school served as an outstanding facility for African-American education in Arkansas; students from all over the state lived with relatives or friends in Little Rock so they could receive a quality education at Dunbar. According to the Sanborn fire insurance maps, Dunbar was built on the same city block as the old Gibbs High School (Gibbs was on the corner of 18th and Ringo, and Dunbar sat on the corner of Wright and Ringo). The old Gibbs Elementary School was just to the west of the high school on the same block, approximately where Dunbar's gym now stands. The present-day Gibbs Elementary School stands on the corner of Cross and 16th Street, two blocks north of the old elementary school. The old high school was still standing as late as 1939 (unknown when it was torn down). Six city blocks ultimately were combined between Cross and Chester streets, 16th Street and Wright Avenue to form one unified parcel of land that now includes the new Gibbs Elementary School, Dunbar, the Dunbar Community Center, the Dunbar Community Garden, athletic fields and the Sue Cowan Williams Library. Dunbar was fortunate to have Charlotte Andrews Stephens, the first African-American teacher in Little Rock and the educator who possessed the longest tenure with Little Rock schools (60 years), on staff as librarian and occasional English and Latin teacher prior to her retirement (Stephens Elementary is named after her). The combination of the modern physical facility, an outstanding faculty and a rigorous academic curriculum resulted in Dunbar receiving accreditation from the North Central Association of Schools and Colleges in 1931. A majority of white schools did not have North Central accreditation at this time, so it was a tremendous boon for Dunbar to earn that recognition of excellence.

In the 1940s, African-American educators in Little Rock grew more and more unhappy with the fact that their salaries were lower than those of white teachers. The NAACP's Thurgood Marshall and Susie Morris, a teacher at Dunbar High School, sued the Little Rock School District for equal pay with white teachers. Attorneys Scipio Jones and J.R. Booker also were involved in this landmark case (Booker Arts Magnet Elementary is named after Booker). Arkansas courts ruled against Morris, but the U.S. Appeals Court overturned that ruling in 1945.

The National Dunbar Alumni Association (NDAA) is comprised of members (former students and teachers) around the country who promote educational, civic and social interests. Local chapters of the national association are based in Chicago, Denver, Detroit, Kansas City, Little Rock, Los Angeles, Philadelphia, San Francisco, St. Louis, Seattle, and Washington, DC. NDAA members are dedicated to perpetuating the "Dunbar spirit of excellence" in their own lives and the lives of others and to preserving Dunbar's history for future generations. The school houses NDAA's Memorabilia Room that preserves artifacts and memories from Dunbar's early years.

This fine old building played a major role in Little Rock's history, and the National Register of Historic Places recognized that role when it added the school to its ranks in 1980. Additions were made to the school in 1952, 1965-66 and 1969. A major refurbishment/addition was completed in 2004, including classroom renovations, a gymnasium renovation/rebuild and a new media center. Dunbar was converted from a junior/senior high to a junior high school in 1955 (after the completion of the new Horace Mann High School) and became a magnet school in 1990, offering a magnet program in international studies. It also offers a special program for gifted and talented students. Dunbar was recognized as a "Magnet School of Distinction" by the Magnet Schools of America in 2004.

Photo: www.americaslibrary.gov

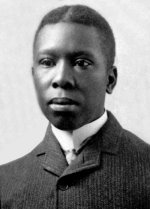

Born in Dayton, Ohio, Paul Laurence Dunbar's work often addressed the difficulties encountered by members of his race and the efforts of African Americans to achieve equality in America. He was praised both by the prominent literary critics of his time and by his literary contemporaries. His mother Matilda was a former slave and his father had escaped from slavery. One of the families Dunbar's mother worked for was the family of Orville and Wilbur Wright, with whom he attended Dayton's Central High School. Dunbar was the only African American in his class, and while he often had difficulty finding employment because of his race, he rose to great heights in school: he was a member of the debating society, editor of the school paper and president of the school's literary society. He published an African-American newsletter, the Dayton Tattler, with help from the Wright brothers. Dunbar's first public reading was on his birthday in 1892.

Oak and Ivy, his first collection, was published the same year. In 1893 he was invited to recite at the World's Fair where he met Frederick Douglass, the renowned abolitionist. Douglass called Dunbar "the most promising young colored man in America." Dunbar's second book, Majors and Minors, propelled him to national fame. William Dean Howells, editor of Harper's Weekly, praised it in one of his weekly columns and launched Dunbar's name into the most respected literary circles across the country. A New York publishing firm, Dodd Mead and Co., combined Dunbar's first two books and published them as Lyrics of a Lowly Life. Dunbar traveled to England in 1897 to recite his works on the London literary circuit. After his return, Dunbar took a job at the Library of Congress in Washington, DC. He found the work tiresome, however, and it is believed the library's dust contributed to his worsening case of tuberculosis. He worked there only for a year before quitting to write and recite full time. Dunbar ultimately produced 12 books of poetry, four books of short stories, a play and five novels. His work appeared in Harper's Weekly, the Sunday Evening Post, the Denver Post, Current Literatureand a number of other publications.

Sources:

LRSD archives.

National Dunbar Alumni Association web site: http://www.ndaaoflra.org/

American Institute of Architects web site, Dunbar High School historical page:

"University President Speaks at Dunbar Opening." The Arkansas News, Old State House web site: ...

The University of Dayton's Paul Laurence Dunbar web page: http://www.plethoreum.org/dunbar/biopld.asp

"African-Americans, Early 20th Century." People and Their Stories page, Department of Arkansas Heritage web site

Sanborn fire insurance maps of Little Rock, Arkansas (showing location of original Gibbs High School and Gibbs Elementary School): available online at http://sanborn.umi.com

"Closed College Index, Arkansas" (web page from R. Brown of Westminster College in Missouri, charting colleges and universities in Arkansas that no longer are operating mIf you have information about a Little Rock school or photographs that you would like to contribute to this project (we will return photographs if requested), please contact us!

Updated March 2005